arrow_back_ios Radio Nizza - Promenade

Past and present of Number Stations: Interview w Andrea Borgnino (RAI)

Podcast in English

calendar_today 24/01/2025 09:41

Original broadcast on 1575 KHz MW From Radio Centrale Milano (Milano-IT)

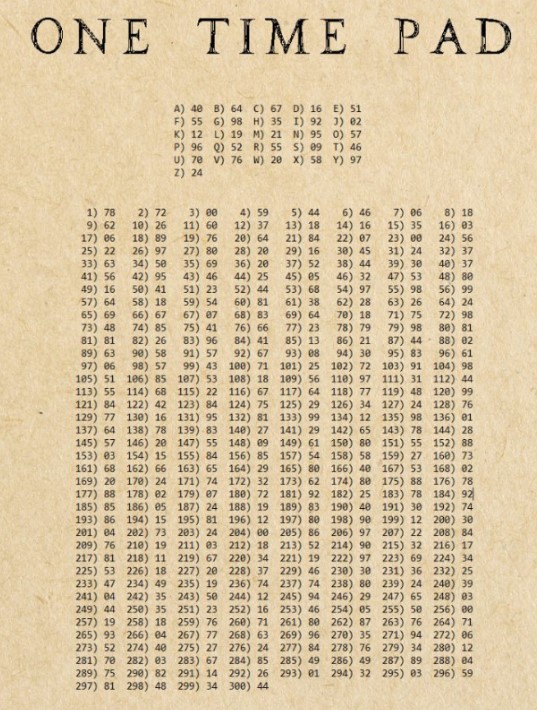

Good Morning to all our listeners on 1575 Medium Waves as well as on Radio Nizza and Centrale Milano. With us today is Andrea Borgnino from RAI, but also a radio enthusiast who will talk about his podcast and its content, specifically the mysterious and famous numbering stations, or radio number stations. At the end of the program, there will also be a small coded message to decipher. Andrea has recently created an incredible podcast about numbering stations--the mysterious stations that broadcast numbers, which are still active today. It is available on the Rai Playsound app and website. Today we're going to discuss it and share further info on these mysterious entities.Radio Nizza: Hello Andrea, and thank you for being with us today.Andrea Borgnino: Hello Marco, and thank you for inviting me.Radio Nizza: Let’s start with a very simple question: for those unfamiliar with number stations, can you briefly explain what they are?Andrea Borgnino: Number stations are peculiar radio stations that started appearing on shortwave bands after World War II, around the 1950s during the Cold War. They seemingly transmit endless lists of numbers or letters--content that appears nonsensical. These are cyclic stations that often broadcast on the same frequencies and have powerful signals. It’s presumed they’re transmitted from large radio centers because they’re easy to receive, even with portable radios.They don’t identify themselves--there’s no voice saying “broadcasting from Italy” or “Germany.” Instead, there’s often just a digitized voice, mostly female, reading groups of numbers or letters.The general belief is that they’re linked to espionage and intelligence activities because spies have been caught either receiving the transmissions or in possession of equipment to do so.My podcast tells the story of these stations in five episodes. It’s a personal story because I discovered them as a teenager when shortwave listening and amateur radio were among my main passions. While listening to shortwave and amateur radio, I stumbled upon them.From there, my passion grew, and in the podcast, I try to explore what they are, their history, and their connection (because there are some) to espionage. In the fourth episode, I talk about stations that are still active today--those you can still hear if you turn on a receiver. This is a world that hasn’t disappeared with the advent of the internet.In the fifth episode, I delve into the many references to these radio stations in entertainment--films, TV series, radio programs, and music inspired by the world of number stations.Radio Nizza: Here’s something that intrigues me as an IT specialist: the cryptographic system of these messages. I believe you mentioned one-time pads--something that’s undecipherable unless, actually, it’s completely undecipherable, unlike regular computer encryption systems. Can you explain how they work and how these pads were distributed?Andrea Borgnino: One-time pads are fascinating because they’re both archaic and incredibly secure. Essentially, there are only two copies of the same sheet containing the code: one with the code generator and the other with the recipient. So, there’s no system more secure. The vulnerability lies in safeguarding the one-time pad. When spies are caught, they’re often found with the pad, but without the counterpart, it’s useless.The fact that the pads need to be generated with truly random numbers is crucial. If the generation isn’t genuinely random, a very powerful computational system could help crack it. But the beauty of this ancient system is that it still works.Radio Nizza: My next question is about transmission frequencies. Shortwave bands are notoriously unreliable--what works perfectly on one day might be completely silent the next, requiring a switch to a different frequency or even a different band. How did they ensure that the network of spies could receive the messages? And how could they share metadata about where to find new transmissions without tipping off unwanted listeners?Andrea Borgnino: To overcome the issue of differing frequencies and reception capabilities, repetition was key.Messages on number stations were, and are, repeated dozens--if not hundreds--of times on various frequencies to ensure the message reaches its intended recipient.I remember when Station 10, which presumably broadcast from Israel and was likely connected to the Mossad, was active. It could be received everywhere. From 2 MHz upwards, every 2-3 MHz on shortwave, you’d find a transmission of the same message. After a while, since each transmission starts with an identifier, you’d hear it repeated everywhere.How did they inform operatives? Well, I believe they had to memorize a pattern--a series of frequencies--and know where to find them.Additionally, the stations don’t broadcast randomly; they have a schedule. Groups like Priyom have created databases of these schedules, making it easier to track or find ongoing transmissions.Radio Nizza: Towards the end of your podcast, you mentioned not giving frequencies because they change often, and you encouraged people to look them up online via enthusiast bulletin boards. However, some frequencies are fixed. For example, UVB is a well-known fixed frequency, and there are likely others. Could you share 2 or 3 frequencies so we can try them tonight?Andrea Borgnino: No, absolutely not. That’s not my role. Frequencies should be looked up on the groups--there’s Priyom, Number Station.org, and at least 3 or 4 other sites listing frequencies.You mentioned UVB, which broadcasts on 4625 kHz. However, it’s not a number station. UVB is a signal that no one has understood to this day. It’s the famous buzzer, which transmits a continuous signal, occasionally interspersed with numbers or letters in the Russian phonetic alphabet.To this day, it’s not classified as a number station. It’s possibly a military station or a propagation beacon. I wouldn’t call it a number station, especially since it broadcasts sporadically, unlike number stations, which consistently broadcast test messages.Radio Nizza: So in your podcast you mention two number stations that ceased to exist the very same day of the Ukraine invasion!Andrea Borgnino: YesThe primary transmitter site is or wasa located north of Rivne, Ukraine. Apart from S06s/E17z, this site also carries digital activity using proprietary systems, both broadcast and point-to-point. One of the identified point-to-point link targets was the Ukrainian peacekeeping mission in the Democratic Republic of the Congo.Radio Nizza: Now for a coded message!Andrea Borgnino: Yes, we’ve decided to create a coded message for our friends on medium-wave radio, both near and far. We’ll also publish a very simple one-time pad on a page of the Radio Nizza website.Here it is: E B V P N B O U F. You can write to us with the solution, and maybe with a reception report at info@radionizza.itRadio Nizza: Thank you very much! Once again, I invite everyone to download the Rai Play Sound app or visit the Rai Play Sound website to listen to this unmissable podcast series about number stations.

Good Morning to all our listeners on 1575 Medium Waves as well as on Radio Nizza and Centrale Milano. With us today is Andrea Borgnino from RAI, but also a radio enthusiast who will talk about his podcast and its content, specifically the mysterious and famous numbering stations, or radio number stations. At the end of the program, there will also be a small coded message to decipher. Andrea has recently created an incredible podcast about numbering stations--the mysterious stations that broadcast numbers, which are still active today. It is available on the Rai Playsound app and website. Today we're going to discuss it and share further info on these mysterious entities.Radio Nizza: Hello Andrea, and thank you for being with us today.Andrea Borgnino: Hello Marco, and thank you for inviting me.Radio Nizza: Let’s start with a very simple question: for those unfamiliar with number stations, can you briefly explain what they are?Andrea Borgnino: Number stations are peculiar radio stations that started appearing on shortwave bands after World War II, around the 1950s during the Cold War. They seemingly transmit endless lists of numbers or letters--content that appears nonsensical. These are cyclic stations that often broadcast on the same frequencies and have powerful signals. It’s presumed they’re transmitted from large radio centers because they’re easy to receive, even with portable radios.They don’t identify themselves--there’s no voice saying “broadcasting from Italy” or “Germany.” Instead, there’s often just a digitized voice, mostly female, reading groups of numbers or letters.The general belief is that they’re linked to espionage and intelligence activities because spies have been caught either receiving the transmissions or in possession of equipment to do so.My podcast tells the story of these stations in five episodes. It’s a personal story because I discovered them as a teenager when shortwave listening and amateur radio were among my main passions. While listening to shortwave and amateur radio, I stumbled upon them.From there, my passion grew, and in the podcast, I try to explore what they are, their history, and their connection (because there are some) to espionage. In the fourth episode, I talk about stations that are still active today--those you can still hear if you turn on a receiver. This is a world that hasn’t disappeared with the advent of the internet.In the fifth episode, I delve into the many references to these radio stations in entertainment--films, TV series, radio programs, and music inspired by the world of number stations.Radio Nizza: Here’s something that intrigues me as an IT specialist: the cryptographic system of these messages. I believe you mentioned one-time pads--something that’s undecipherable unless, actually, it’s completely undecipherable, unlike regular computer encryption systems. Can you explain how they work and how these pads were distributed?Andrea Borgnino: One-time pads are fascinating because they’re both archaic and incredibly secure. Essentially, there are only two copies of the same sheet containing the code: one with the code generator and the other with the recipient. So, there’s no system more secure. The vulnerability lies in safeguarding the one-time pad. When spies are caught, they’re often found with the pad, but without the counterpart, it’s useless.The fact that the pads need to be generated with truly random numbers is crucial. If the generation isn’t genuinely random, a very powerful computational system could help crack it. But the beauty of this ancient system is that it still works.Radio Nizza: My next question is about transmission frequencies. Shortwave bands are notoriously unreliable--what works perfectly on one day might be completely silent the next, requiring a switch to a different frequency or even a different band. How did they ensure that the network of spies could receive the messages? And how could they share metadata about where to find new transmissions without tipping off unwanted listeners?Andrea Borgnino: To overcome the issue of differing frequencies and reception capabilities, repetition was key.Messages on number stations were, and are, repeated dozens--if not hundreds--of times on various frequencies to ensure the message reaches its intended recipient.I remember when Station 10, which presumably broadcast from Israel and was likely connected to the Mossad, was active. It could be received everywhere. From 2 MHz upwards, every 2-3 MHz on shortwave, you’d find a transmission of the same message. After a while, since each transmission starts with an identifier, you’d hear it repeated everywhere.How did they inform operatives? Well, I believe they had to memorize a pattern--a series of frequencies--and know where to find them.Additionally, the stations don’t broadcast randomly; they have a schedule. Groups like Priyom have created databases of these schedules, making it easier to track or find ongoing transmissions.Radio Nizza: Towards the end of your podcast, you mentioned not giving frequencies because they change often, and you encouraged people to look them up online via enthusiast bulletin boards. However, some frequencies are fixed. For example, UVB is a well-known fixed frequency, and there are likely others. Could you share 2 or 3 frequencies so we can try them tonight?Andrea Borgnino: No, absolutely not. That’s not my role. Frequencies should be looked up on the groups--there’s Priyom, Number Station.org, and at least 3 or 4 other sites listing frequencies.You mentioned UVB, which broadcasts on 4625 kHz. However, it’s not a number station. UVB is a signal that no one has understood to this day. It’s the famous buzzer, which transmits a continuous signal, occasionally interspersed with numbers or letters in the Russian phonetic alphabet.To this day, it’s not classified as a number station. It’s possibly a military station or a propagation beacon. I wouldn’t call it a number station, especially since it broadcasts sporadically, unlike number stations, which consistently broadcast test messages.Radio Nizza: So in your podcast you mention two number stations that ceased to exist the very same day of the Ukraine invasion!Andrea Borgnino: YesThe primary transmitter site is or wasa located north of Rivne, Ukraine. Apart from S06s/E17z, this site also carries digital activity using proprietary systems, both broadcast and point-to-point. One of the identified point-to-point link targets was the Ukrainian peacekeeping mission in the Democratic Republic of the Congo.Radio Nizza: Now for a coded message!Andrea Borgnino: Yes, we’ve decided to create a coded message for our friends on medium-wave radio, both near and far. We’ll also publish a very simple one-time pad on a page of the Radio Nizza website.Here it is: E B V P N B O U F. You can write to us with the solution, and maybe with a reception report at info@radionizza.itRadio Nizza: Thank you very much! Once again, I invite everyone to download the Rai Play Sound app or visit the Rai Play Sound website to listen to this unmissable podcast series about number stations.